by Nancy K. Bereano

Hospicare and Palliative Care of Tompkins County tries to meet the medical, emotional, and spiritual needs of its patients and their families, embracing the fullness of life as its clients move toward the inevitability of their deaths. The facility is located in a beautiful country setting a half mile off one of the county’s main roads, a handsome structure expanded several times since it was built in 1995, the first free-standing hospice residence in New York State. The six private patient rooms look out on volunteer-tended gardens and walkways, a pond with reappearing seasonal waterfowl, and stone-paved meditation paths. There is administrative office space and an airy public front room spacious enough to easily hold a grand piano, a large table for impromptu meetings and holiday celebrations, comfortable couches, and a small library with books available to residents, staff, and visitors alike.

I was nervous when I applied and was accepted as a Hospicare volunteer. I didn’t know the details of what I would be asked to do, what would be expected of me. As it turned out, the training sessions (two full weekends and several lectures) were more of a way for new volunteers to learn about the institution, the regulations (city, state, and federal) within which we would be working, the organization’s culture, time expectations, and an opportunity to engage various members of the staff.

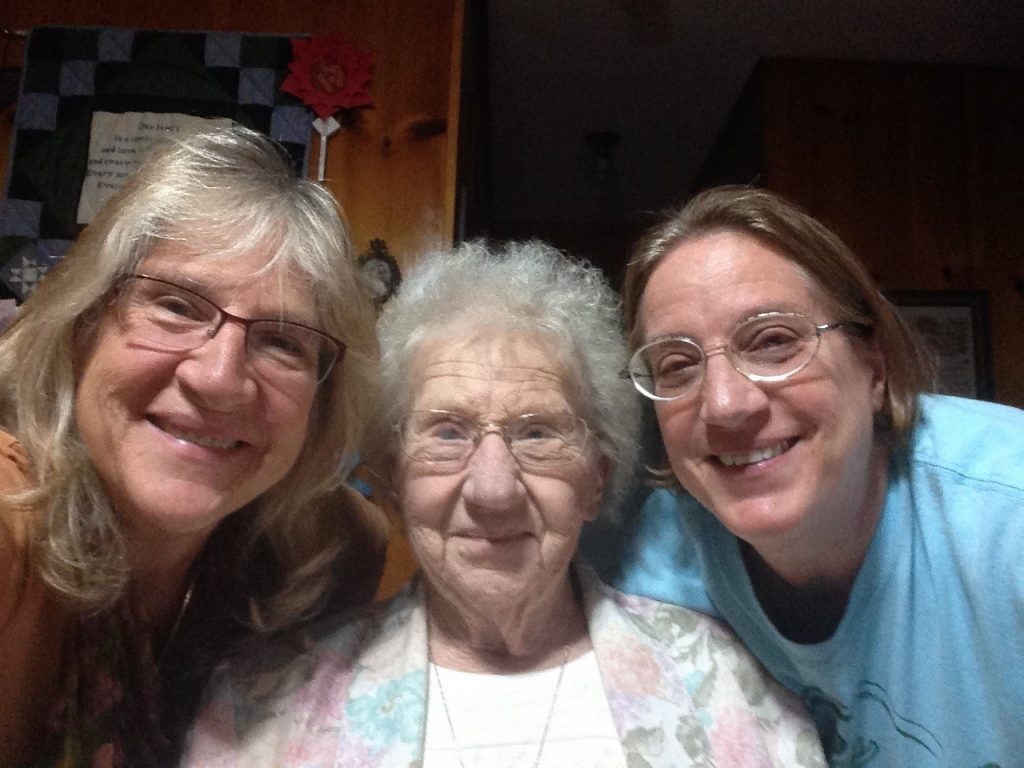

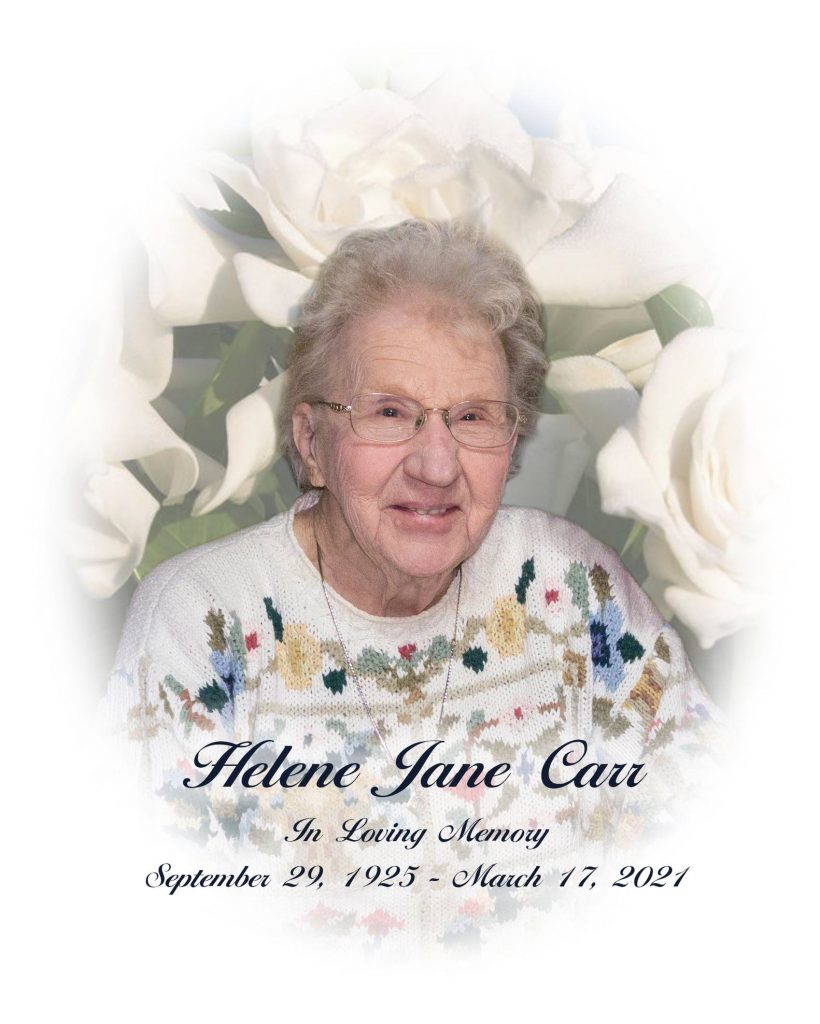

Volunteers sign up for four-six hours of work per week from an extensive list of possible assignments. Cooking for one or all of those in the residence, one-on-one visits with patients, providing relief for caretakers, running errands, and, much to my surprise, at the time I volunteered there was a recently instituted oral history project—recording the stories of Hospicare clients for their families. This seemed made for me. I had loved getting to know details about my authors’ lives as we worked together on their manuscripts. It often added layers of meaning to their words. Since none of what I was now signing on to do was for publication, only for the memories and comfort of the dying person’s family, it required, more than anything, someone who was a good listener and an insightful questioner. I thought that my work at Firebrand made me well-suited for this. Little did I know that I would meet, work with, befriend, and several times be welcomed into the families of some remarkable people. Almost all of the Hospicare clients were surprised at their families’ desire to have a personal history undertaken since, almost to a person, they thought there was nothing particularly special to tell. My takeaway was quite different: While it was true that no one was famous, each of them was unique, and as they approached the end of their life, it was often difficult to get them to reflect on what they had done, what had been important to them. But there were times when my emotional involvement was strikingly similar to what I had experienced working with an author.

I spent time with some two dozen people over the course of my three-plus years of personal history volunteering. Most of that took place in their homes, which added an additional level of getting to know them. No marathon editing sessions as with authors. Usually only a half hour at a time of working together, conserving their limited strength. Each meeting with a new person was like receiving a manuscript in the mail: I wasn’t quite sure what I would find when I opened the package/knocked on the door.

I remember the stay-at-home housewife who wistfully conjured up dancing to the music of one of the visiting big bands in Kansas City when she was still a teenager; and the farmer who talked about meeting Eleanor Roosevelt at a union organizing event in New York City when he hadn’t yet “settled down”; and the young man in his thirties who had banked his sperm when first diagnosed with cancer and was hoping he’d live long enough to make a photo album for the child his wife would carry after he died. (I cried as I walked to my car when each of the too few sessions with him ended.)

These were different kinds of deadlines from the production and editing ones I had lived with and worked my life around at Firebrand. There was nothing I could do to slow down disease, to rework schedules to accommodate changed medical conditions. These were not situations where my skill and determination could alter what I had decided were the drop-dead dates that would allow scheduling to proceed apace. (While I had often used the “drop-dead date” phrase in a book production timeline, it catches me up short as I write this.)

People died. Sometimes that was extremely sad. Occasionally it was emotionally devastating, and I had to take a step back from the work for a while. But there was something about knowing from the beginning what the ending was going to be that made it a different kind of experience. I was traveling a path with the person, if only in a minor way, and in my being there I was part of both their life and their death. The stories I heard and the relationships that grew as I asked questions and recorded our exchanges while they were living their lives, while they were dying, made my life richer.

The things I experienced and learned were moving and difficult: How very few people were able to or interested in talking about their life. Maybe because being a Hospicare client meant that they knew their life was ending and it was more than they could handle. But often it seemed as if they couldn’t acknowledge that their life had really mattered. When I asked what the things were that they had done that were important to them, that they wanted their loved ones to remember about them, I was usually told: “I didn’t do anything special. I really don’t have anything particularly interesting to tell.”

How different from my authors who believed that their stories, their truths, needed to be told, who were fairly brimming over with the desire to be listened to, to be seen and heard.

Nancy K. Bereano, is the founding editor and publisher of Firebrand Books, the groundbreaking and award-winning lesbian and feminist press (1985-2000) with 105 titles on its list, including work by Dorothy Allison, Alison Bechdel, Leslie Feinberg, Jewelle Gomez, and Audre Lorde. With a long grassroots activist history, both within and outside the LGBTQ community, Nancy is NYC born and raised but has lived in Ithaca for the past 54 of her 80 years. Although she has mentored many writers as editor and publisher, Fanning the Flames: The Making of (a) Firebrand, a personal/political memoir, is her first book-length manuscript. The building on the Commons in which Firebrand’s office was located was recently granted historic preservation status.